The Story Of Highlands

Compiled and Edited by James W. Brydon

From 1525, when Giovanni de Verrazano first came to explore the area, through the 17th and 18th Century Dutch and English settlers, and up to the 20th Century, the first sight of land for the many hundreds of thousands of immigrants and visitors to our shores was the rugged and thickly wooded hills of the Highlands of Navesink. Rising majestically above the turbulent waters of the Shrewsbury and Navesink Rivers and Sandy Hook Bay, Mt. Mitchell, at 260 feet above sea level the highest point on the U.S. Eastern Seaboard, has welcomed many of the most historic and legendary figures in the development of America.

As a haven for many American Indian tribes; as the stopping place for such historical heroes as Verrazano, Estevan Gomez, Henry Hudson, Capt. Joshua Huddy, the Gloucester fishing fleets, the U.S. Armed Forces, and the infamous Rum Runners; as the setting for such legendary figures as Capt. William Kidd, and the bewitched "Water Witch" and "Lust in Rust" of James Fenimore Cooper's flowing imagination; and as a mecca for fishermen, bathers, hikers and artists, the hills of Highlands have stood towering in the fore front of the development of the New Jersey Shore. The history of Highlands is as diverse as the varieties of trees, wild flowers, fishes and people that populate its woods, shore and waters - no area of the Jersey Shore has played so important an historic role, nor gone through as many changes as the little town of Highlands and the ever changing spit of land called Sandy Hook.

Situated just twenty-six miles from New York City, to which it is connected by land and water routes, Highlands today is a major attraction to fishermen, bathers and other lovers of the shore, and to those who delight in the very best of seafood dinners. The docks and marinas of Highlands provide safe harbor for every type of craft imaginable, its restaurants are among the most famous on the shore, and the newly established Gateway National Recreation Area on Sandy Hook provides over thirteen miles of ocean and bay bathing for summer visitors.

The history of Highlands and Sandy Hook is filled with romance, glamour, heartbreak, treachery, dedication and adventure. Let's go back through thousands of years of geologic time to begin our look at the life of this "good fishing place" which was once known as one of the most beautiful spots in the world.

Mt. Mitchell, rising 248 feet above the town of Highlands and 260 feet above sea level, is the highest point on the Atlantic Coast of the United States. Our present day coastline, for all its year-in and year-out changes, is relatively stable - basically unchanged for many centuries. At one time, though, eleven thousand years ago, the seas of the "Jersey Shore" washed most of the Coastal Plain on a line just to the south and east of the modern cities of Camden and New Brunswick. Out in the ocean were scattered islands - the occasional "high" spots such as Mt. Mitchell and other, lower hills of Highlands. At that time, during an interglacial period, the sea level was 300-600 feet higher than at present because of melting glaciers pouring into the sea. Then, about four thousand years ago, as the waters receded and further geologic upheavals pushed the land mass of the continental shelf upwards, the foreboding topography of the hills of Highlands was exposed to dry in the sun and become alive with lush vegetation.

The Highlands hills fall away quickly, precipitously in spots, to the Bay on the north, the Atlantic Ocean on the east and the Navesink River on the south.

Today, the narrow Peninsula called Sandy Hook is the only barrier preventing three thousand miles of rolling Atlantic Ocean from breaking at the foot of the hills of Highlands - though there were many times when the furious waves were able to punch their way through in spots. But long ago there was no Hook at all. The Navesink and Shrewsbury Rivers flowed directly into the sea east of the Highlands. Slowly, though, prevailing currents pushed a narrow spit of land to the north, uncertainly moving across the river estuaries - although not completely closing them. The spit lengthened and, out beyond the full influence of the rivers it widened. Then, incredibly, the sands, incited by the mischievous ocean, stood up to the Navesink and Shrewsbury Rivers and closed their mouths, forcing them to flow northward inside the new Hook. Today, Sandy Hook is a geological adolescent, still growing; its area has quadrupled since the Hook was first surveyed in 1685 and its shape is in constant change. But the building of a sea wall over eighty years ago has prevented the angry waves of the capricious Atlantic from smashing through to the River inlets again. The oldest known route of travel to the coast, the Minisink trail, began on the upper Delaware River and wound its way through northern New Jersey to a termination point on the Navesink River. This trail was used by Indians, predominantly those of the Algonquin and Lenni Lenapi nations, from throughout New Jersey to retire to their summer villages to fish and clam and pick beach plums. Of the many tribes that came to "Navesink" - which means "good fishing place" the most permanent were the Newasunks, Raritans, and Sachem Papomorga - Lenni Lenapis. These tribes were the ones most written of and traded with by the early white visitors to the area who continued for many years to call the area by the Indian name "Navesink."

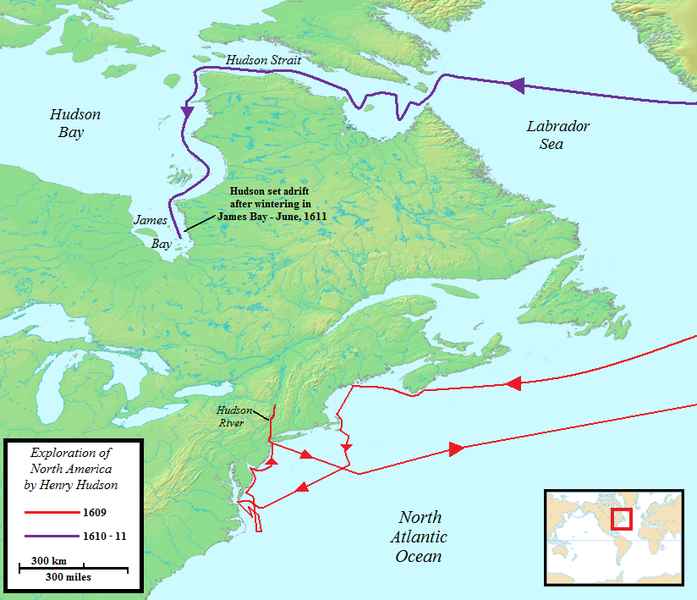

In 1524, the Highlands of Navesink were seen, for what was probably the first time, by a white man - the explorer Giovanni de Verrazano. He wrote of natives "clothed in feathers of birds of various colors" and of naming "a small mountain which stands by the sea" - probably the "mountain" upon which the Twin Lights now stands. Also in 1524, Estevan Gomez, a Portuguese exploring under the flag of Charles V of Spain, visited the Highlands of Navesink and drafted what were probably the first maps of the area. His maps were more than likely the only in existence in Europe for almost a century, and it is doubtful that they were very widely circulated among the jealous and protective ruling kings. It was on these maps that Sandy Hook was first drawn - it was labeled "Cabo de Arenas" or "Cape of Sands". So, when Henry Hudson sailed with his ship, the Half Moon, and his crew into the Sandy Hook Bay, he made history as the first real explorer of this area. The log book of one of his crew members, named Robert Just, is the first bit of real estate promotion for the Highlands: "This is very good land to fall in with," he wrote, "and a pleasant land to see. Our men went on land, so they went up into the woods and saw great stores of very goodly oaks and some currants". (Probably meaning wild plums or wine berries according to Fletcher Pratt, Highlands historian). Another crew member, John Colman, became the first man whose life was taken in the making of the State of New Jersey, when he was killed ~'with an arrow in his throat" by frightened Indians coming upon his scouting party in the woods. But Henry Hudson's fame in the history of Highlands has nothing to do with oaks, currants or loss of life - rather with the most basic element of life, water. The rugged and thickly wooded hills of Highlands are only moderately changed in appearance since that day in September, 1609, when he dropped the Half Moon anchor and sent his men ashore to seek water be fore continuing his voyage up the river which bears his name. Deep in those trees is the site of the flow of clear, cool spring water from which Hudson's men refilled their casks. Even up to 1900, sailing ships stood in behind the Hook to get water from "The Spout"; Thomas H. Leonard, in his 1923 History, re called the 300 sails of the New England fishing fleet clustered on the Bay a "sight beyond" as they awaited a favorable wind after getting Highlands water. Though nature has brought about the overgrowth of the trails from the bay, the stone retaining walls are crumbling, and the water has been contaminated by time and population, the sight of Henry Hudson Springs is still marked and provides shady refuge to the Spring and Summer hikers that follow the winding road through the hills.

Several years after Henry Hudson's visit, around 1613-1615 , the Highlands of Navesink became of special interest to Dutch traders. They traded with the Navesink Indians and charted the waters. One, William Reape, made a deal with the Sachem Popomorga, getting land enough for several counties in exchange for rum, powder, and blankets. It is doubtful as to whatever became of Reape's claim to the land, as later dealings fail to mention him at all. It was around this time that "official" names began to be applied to Sandy Hook and the Highlands hills. Adrian Black, a waterway chart-maker, named them, collectively, "Rodenberg Hoeck" meaning '~Red Hills Hook". Later Dutch settlers re named it "Rensselaer's Hoeck", after one of the sponsors of the New Netherlands settlement.

In 1664, British settlers took over and renamed the settlement "Portland", probably due to its resemblance to the town on the south coast of England of the same name, and which terminated in a similar hook formation. The hills of Highlands were always the first landfall for ships voyaging from Europe to the New York area, and, according to historian Fletcher Pratt, by 25 January, 1664, title to the ground on the Highlands of Navesink was being purchased from the Indians by a group including James Hubbard, John Bawne, John Tilton, Jr., Richard Stout, William Goulding and Samuel Spear - some of which names still stand among the list of the borough's residents. The price was rather more than that paid for the Island of Manhattan. This could have been due to the local Indians being shrewder business men than their New York brothers or because the fishing was so much better here. At any rate, according to Mr. Pratt, there seems to have been some difficulty about this sale, because Governor Richard Nicolls had already granted the "Monmouth Patent", covering the Highlands of Navesink, and soon after the proprietors of East Jersey, under a Royal Grant, issued the same grant to other patentees; but there is no record of how the matter of title was settled, in court or out of it. The clear point is that in 1677, Richard Hartshorne purchased from the Indians, with the proprietors of East Jersey as overseers, for the usual beads, guns, and firewater a 2,320 acre tract of land which gave him control of nearly all of Sandy Hook and the Highlands - then called "Portland Poynt" - and made him and his family the first permanent settlers of this area. The lease specified that Hartshorne was "to enjoy the whole range and benefit of Herbage and feed for hogs and cattle with privilege of fowling, fishing, etc., upon the beach called Sandy Hook, for 21 years rent: 1 pepper corn, yearly, if demanded. . ." This agreement has given us an interesting insight into the Indians' mode of life and their conflict with the white man. It reads, in part, "Whereas the Indians pretend that formerly, when they sold all the land upon Sandy Hook they did not sell, or did except liberty (retained the right) to get plumbs (beach plums) when they please, and to hunt upon the land and fish, and to take dry trees that suited them for cannows (canoes). . . "I, Richard Hartshorne, . . . for peace and quietness sake, and to the end that there be no cause for trouble with the Indians and that I may not for the future have trouble with them as formerly I had, in their dogs killing my sheep. . . I have agreed (to their) plumbing on Sandy Hook, hunting, fishing, fowling, getting cannows, etc.. (they in turn to convey to me) forever... Sandy Hook (and) lands adjoining to it, (the Highlands of Navesink) in consideration the said Richard Hartshorne hath paid unto the said Jawavapon, thirteen shillings

It is a tribute to Richard Hartshorne and the other early settlers of the Bayshore area that in settling here they spilled not a drop of Indian blood in battle, nor did they take an acre of land without the consent of the Indians. Any discussion of the history of the Highlands of Navesink has got to include, also, the history of Sandy Hook. The two are inseparable, though physically separate - they are a team; militarily, in navigational importance, in fishing and recreation, and in the economic growth of the area. We have already traced the development of Sandy Hook geologically through the movement of tides and currents and we have seen it charted as Cabo de Arenas - now let's look at its development in relation to the first stirrings of growth of the New World.

Sandy Hook, by nature of its geographic location in lower New York Bay, is one of the most famous navigational landmarks on the Eastern Seaboard. Extending northward into lower New York Bay beside the original and, until 1899, the only deep water channel into New York Harbor, its strategic location has in varying degrees involved it in the discovery, economic development, and military history of this region.

Some who gazed across the Highlands to New York recognized the true destiny of Highlands and the Hook - to warn the city of an approaching enemy, to fight that enemy if he arrived, and, in days of peace, to guide ships into the harbor. As settlement and control of the region progressed as New York evolved into an important trade center in the New World, the need to permanently identify the existing channel was obvious; as was the need for a lighthouse on Sandy Hook to prevent any more of the costly wrecks that had already taken place by 1761 in violent storms, for which the Hook is notorious.

As early as 1680, Edmund Andros, English colonial governor of New York and New Jersey, which was then one province, planned to build a beacon on the Hook, it must eventually have been destroyed by the sea or outlived its usefulness, for, on 16 May, 1762~, the New York Merchants purchased a four acre site from the Hartshorne family for a light house. On 11 June, 1764, the Sandy Hook Light House was lighted for the first time and it still exists today - a National Landmark as the oldest operating light house in the United States. The City, and those who come to it by sea, have depended on that light since 1764. Of all the legendary ships that found refuge in the Sandy Hook Bay, none loom larger in tradition and mystery than the Buccaneer Ship of Captain William Kidd. Many a tale-weaver, down through the years, has told of the flying of the skull and crossbones and the Kidd treasure buried out on Sandy Hook by a lone pine tree or in the sands of Highlands. or resting on the bottom of the Bay where he tossed it to escape a Man-o'-War. No amount of scoffing can make the townspeople of Highlands ever believe that these legends are not true.

One of the most sensational episodes in the history of Highlands is the great gold rush of 1948. On 19 April of that year, William R. Cotrell, a 75 year old lobsterman, found actual and visible ancient gold coins, about the size of half-dollars, on the beach off Cedar Street. Fletcher Pratt tells us that for days all business ceased as Highlanders and foreigners sifted the sands in frenzied search for more of Capt. Kidd's lost treasure. When the rush was over a considerable amount of valuable collectors' items were recovered. Though the value of the coins cannot be disputed, their link to Capt. Kidd can be; Kidd was captured and hanged in 1701, and most of the recovered coins bore dates of 1730 and later. This makes it seem exceedingly likely that they actually belonged to the treasure chest of a British frigate, H.M.S. Looe of forty-four guns, which dragged her anchor and went ashore in the lower bay in 1744, before the Hartshornes had built their big house or before there was anyone else to watch the proceedings except a few uncomprehending Indians of the Nawasunk tribe.

If some say Captain Kidd never really unfurled a sail off the Hook, it remains a fact that no one ever delves into the region's story without coming up with at least a mention of his name.

Beyond legend is the important role, based on historical records, that the hills of the Highlands of Navasink and Sandy Hook played in the American Revolutionary War. A vital strategic point for both the British and Colonial Armies, the area was constantly trafficked by the movement of troops of both sides.

When the British fleet arrived off Sandy Hook on Saturday, 29 June, 1776, sympathizers with the British cause, mainly from Monmouth County, fled to Sandy Hook via Highlands in large numbers. These so-called "Loyalists" built fortifications and with the help of the British, were able to hold Sandy Hook for the remainder of the Revolutionary War.

Perhaps the most widely known event relative to Sandy Hook, Highlands, and the Revolution happened during 1778 after Britain learned that France had acknowledged the independence of the young United States. At the time Britain had its main army divided between Philadelphia and New York and it was decided to consolidate these two forces at New York.

The British were short of ships and it was planned to march the Philadelphia force of over twelve thousand, across New Jersey to New York. General Sir Henry Clinton was in command of the army, which departed Philadelphia on 18 June, 1778.

General George Washington started in pursuit of Clinton with some of his force that same day from Valley Forge where they had spent their infamous harsh winter. The next day the entire American army of about the same size as the British, was on the march.

The two armies met at Freehold, now the Monmouth County Seat, where the important Battle of Monmouth was fought to a draw on Sunday, 28 June, 1778.

After the battle, Clinton continued his journey through Monmouth by way of Middletown, then on toward Sandy Hook. On top of Chapel Hill, and from the Navesink River to Sandy Hook Bay, Clinton deployed his force while a pontoon bridge was being built from the Gravelly Point section of Highlands across the tidal stream at the base of Sandy Hook.

On 5 July, 1778, a week after the battle, as recorded in General Clinton's own narrative of the war, "the King's army descended from the High (lands) of Navesink, where I caused them to encamp, and embarking in transports (off Horse Shoe Cove) were conveyed to their respective stations on Staten, York, and Long Islands."

The Loyalists stayed in control of Sandy Hook even after the war was ended by the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown on 19 October, 1781.

The Loyalists waited there on the Hook until the following year when they sought refuge in New York City, which was still occupied by the British until the American Revolution was ended by the Treaty of Paris on 3 September, 1783.

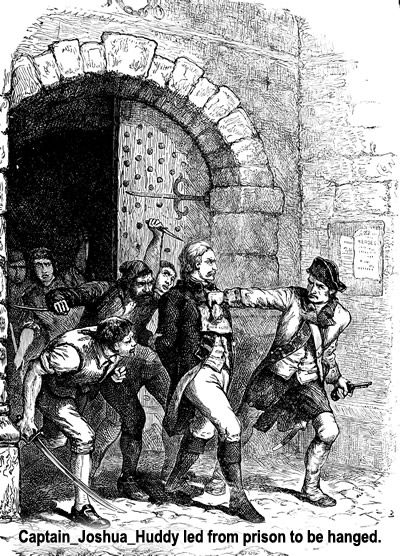

Highlands had its own Revolutionary hero, Capt. Joshua Huddy. He was the eldest of seven brothers, a member of the Monmouth County branch of the Continental Militia and a great hunter of the gangs of Tory (Loyalist) refugees who plundered this whole section of the state in their search for American rebels. They made him a particular target of their detestation and several times laid plans to kill him. In 1780, on one of the Loyalists' many raids from Sandy Hook, one of these plans practically succeeded when they set fire to his home in Colts Neck. Huddy, who was within and armed, agreed to surrender if they would help him to put out the fire. They did agree and started off with Huddy as a prisoner; but the burning house had attracted the attention of his neighbors, who sent for help to the nearest guard station, whereupon the local militia all took their guns down from the mantelpiece and boiled out in pursuit. They overtook the vengeful Tories before they reached their boats at Black Point, Rumson, and during the row, Huddy knocked out the man who was holding him, jumped overboard, and escaped.

Two years later the Loyalists caught up with him during a raid and minor battle at the salt works at Toms River, then known as Dover. Huddy was carried off to the Sugar-House Prison in New York City and then transferred in irons to a guard ship at Sandy Hook where the British held him for a short time. On 12 April, 1782, a party of Tories carried him to Gravelly Point - Highlands - where he was allowed to write his will. Charged with having cruelly put to death one Captain Philip White, Captain Joshua Huddy was hanged. (Philip White had been captured by rebels earlier in Long Branch and shot while being transported to Freehold. Huddy was not involved in the shooting, having been in a British prison at the time, but was hanged merely as an expression of retaliation). Huddy's body was found by a party of patriots, who carried it to Freehold and buried it there.

General George Washington, when told of the hanging, demanded the British turn over to him Captain Richard Lippencott, a Monmouth County Loyalist said to be responsible for the hanging. This demand was refused and a substitute was offered, who was later released as a "humanitarian act" of the Continental Congress.

A monument bearing a plaque to Captain Joshua Huddy now stands in a small park which bears his name at the foot of Water Witch Avenue in the Highlands near the spot where he was hanged.

In 1796, hotelman Nimrod Woodward bought eight hundred acres of land on Sandy Hook and built what was probably the first hotel in the Highlands of Navesink area. The first hotel to be built in the Highlands proper was the "White House" also built by Wood ward in 1815.

The hotel business thrived from '96 until the War of 1812 caused a temporary halt in the operations due to the use of the roads then on the Hook to bring supplies to the Navy flotilla stationed there and to the workmen building new fortifications. Since the War of 1812 was fought over encroachment of British shipping and the imprisonment of American seamen, it naturally followed that Sandy Hook would be brought into play to provide defense for the vulnerable New York Harbor. From this time. and for a long time afterwards, strong works were employed in the defense of Sandy Hook - though the British did maintain an effective blockade of the Harbor. Whenever British ships were sighted in Sandy Hook Bay, pre arranged visual signals were flashed from the Hook to Highlands, then to Staten Island and to New York to alert defenses there.

After peace was signed with Britain in 1814, the Highlands of Navesink once again began to bustle with the tourist trade. Many new hotels were built on Sandy Hook and on the hills of Highlands, and many new homes sprang up - mostly belonging to visitors from the cities of New Jersey and New York. Boating became a major past-time in the area and the Bay was constantly alive with the glisten of blowing sails. Shipping was in its prime and the romance of the sea was the common denominator of the era's literature.

The Water Witch was just one of those fanciful sea-going adventures - launched from the pen of James Fenimore Cooper, author also of the great American classic, Last of the Mohicans, and considered America's first real novelist.

As for the Water Witch, she was a sea-going lady. Cooper drew that full-rigged "skimmer of the seas" out of thin air, writing hastily in a Paris hotel in 1830, before the elusive ship escaped him altogether. The Water Witch is one of America's finest sea legends and her sailing lanes unmistakably were the waters at the foot of the High lands of Navesink.

Cooper remembered well the Highlands where he often had visited, and he transplanted his memories into his novel as a back ground for the bewitched ship. Its setting was Woodward's hotel, where he had spent much time and called, in the novel, "Lust in Rust" - the ruins of which could still be shown to visitors as recently as 1913. Today nothing remains - not even the sign, "Water Witch" at the long-gone railroad station in the section of Highlands that gave James Fenimore Cooper the name for his book. But the Highlanders remember - especially those who live in Water Witch and tell of the book written about their community.

The lore and legend of the sea is filled with graphic depictions of sea-fight and shipwreck; and the Highlands of Navesink has its share of romantic narratives. But the real tragedy of death on the sea is as much a part of its history as beach plums and musket fire. Though the beacons on Sandy Hook and the Highlands had been operating for many years, the tragic loss of life and cargo in violent storms, for which it must be repeated that the Hook is notorious, necessitated the formation of the Lifesaving Service in 1848. The Service was at first manned by volunteers, mostly hardy shore fisher men from Highlands, who, when needed, would brave the crashing surf in small, fragile boats to drag rescue lines to the passengers and crews of hapless ships.

Probably the most tragic of the shipwrecks was that related to us by Fletcher Pratt - the four-masted schooner Kate Marquise. On 12 April, 1890, the captain and eight crewmen of the Kate Marquise were lost when the ship broke up in an hour, with no one being able to get ashore, in spite of the heroic efforts of a Highlander named Charles Pederson, who waded out with a line through boiling surf.

Highlands continued through the 1800's, despite the Civil War when fortifications continued to be improved on Sandy Hook, to grow in esteem as a resort area and to attract the most renowned of America's citizens. Walt Whitman, one of America's most famous poets, celebrated his excursions to Highlands in his journals and a group of his poems entitled, "Fancies at Navesink". And during the period from 1880-1900 Highlands was considered America's fore most and most elegant watering place.

Many hotels, pavilions and clubs had grown up in the Highlands by 1880, and its scenic effects and scenic wealth had made it an ideal all-year residential town. This was the beginning of a new era for Highlands - a romantic era. Once merely the first glimpse of America for millions of immigrants - all the way back to the 17th Century Dutch - the hills were now alive with people attracted by the feeling that the Highlands is one of the most beautiful locations in the world.

Coach, railroad, steamer, and sailing ship service brought Sandy Hook and Highlands to their prominence as a vacation spot in the post - Civil War prosperity. Though drawn by the pristine loveliness and the ever-present loneliness, the new visitors found the enduring thing to be the essential romance of the place, a place touched by the sea, yet apart from it - located as it was in the second richest agricultural county in the country at the time. Nothing - wind, storm, hurricane, even people, changed the Highlands much. Its character was unmatched - the familiar and the mysterious existed side by side.

There sprung up at the Highlands a county of the arts. Pioneered by John Webster (producer?) New York's favorites of the theatrical profession built their summer homes on the hill from the Twin Lights to the Navesink River Bank (Portland Road and Highland Avenue) and, attracted by the scenic wealth - particularly the spectacular view of Sandy Hook and New York from Lighthouse Hill (the Hook here being easier to see than any strip of the Jersey Shore) - many artists of the time also built their homes here. So popular was the Highlands that Harper's Magazine sent a journalist down nearly every summer in the 1870's and 1880's to write of the fascinating parade of fishermen and artists, yachtsmen and clammers, and of the natural wonders of the shore and mountains.

The first steamboat to Highlands was the Saratoga, Captain Joseph King, the date being 1830. The Saratoga was built by Cap King and he, along with Peter W. Schenck (related to Peter Schenck, the first postmaster of Highlands) and four others, formed the Monmouth Steamboat Company. This was the beginning of a era that lasted for over one hundred years.

Most of the steamboats were side wheelers (two attempts use stern wheelers failed when the vessels continually went aground) and these made as many as four round trips daily from New York, Highlands, Red Bank, Little Silver, and Long Branch. Hotels, merry go-rounds, picnic groves and dancing pavilions lined the shores of the Shrewsbury River at Highlands and Sandy Hook; but the big attraction was the floating theater on the Shrewsbury, which performed Gilbert and Sullivan operettas and musical comedies to audiences of over two thousand.

During the years, the Mary Patten, Little Silver, Thomas Patten, and Elberon began to make their runs, and these four became the famous Patten steamers of the heyday of steamboat operations.

The 1920's were boom years for the steamboat era in Monmouth County waters. In 1926, for example, two companies alone reported carrying more than one million passengers between New York and New Jersey! However, by 1930, because of the tremendous development of our national highway system and the popularity of the automobile, the operations of many of these vessels became economically impractical.

Sadly, the century-long era of steamboat operations on the Shrewsbury and Navesink Rivers came quickly to an end as the Little Silver docked for the last time in 1932.

But the steamboats and sailing ships were not the only means of transportation available to the millions of visitors to Sandy Hook and Highlands. The Seashore Railroad was built on the Sandy Hook peninsula in 1865, and James Schenck established a ferry service across the river, from Highlands to his hotel on the Hook, which was maintained until the bridge was constructed in 1872. The bridge was a drawbridge erected by the Highlands Bridge Company; it was 1,452 feet in length, 18 feet in width, with a draw of 186 feet, and was built at a cost of $35,000.00. It was formally opened on 5 December, 1872 and continued in use until July, 1875 when a schooner ran into the draw and disabled it - in which condition it remained for three years. The Monmouth Bridge Company was formed, bought the bridge, repaired the draw, making it 194 feet in length, and opened it for travel on 27 June, 1878.

By 1883, the railroad came to Atlantic Highlands and in 1892 the old draw bridge at Highlands was torn down and a new railroad bridge was built by the New Jersey Central Railroad Company for their coastal line. This new bridge for rail, vehicular, and foot traffic was opened on 30 May, 1892 - beginning another great new era for the Highlands.

Sailing ships, steamboats, ferries, railroads, and trolleys connected the ever-popular Highlands to the rest of the county and the state. Soon, from out of this hustling and bustling era, the Borough of Highlands was to be born.

High up on Lighthouse Hill, keeping a silent watch over the growing life and history of Highlands and the Hook below, stood the stately Twin Lights. Except for Bunker Hill (which cannot be seen from the sea) and Plymouth Rock (which is now well inland) mere is no more historic spot on the Atlantic Coast than me High lands Twin Lights - the only twin light house in the world - which has played a role in dozens of historic occasions. Among its "firsts" was - besides its being the first twin light house - the first electric powered light, the first glimpse of America for incoming ships, the first to use the Fresnel lens, the first to use wireless telegraphy, and the site of the first experiments with radar.

Light House Hill (also known as Beacon Hill) was employed as a site for a beacon as early as 1746, when England was in conflict with France in the War of Austrian Succession, and the colonies of both were up for grabs. The beacon - whale oil burned in pots - was not to welcome sailors, but to warn citizens that the French were coming up the harbor and it was time to take down the musket from over the fireplace. During the American Revolution, the beacon served the same purpose, only Britain was the enemy.

The beacon was a visual signal system using large balls in day light and the burning whale oil pots at night - hoisted upon poles said to have been 108 feet high. Signals were raised or lowered according to a code which was read by telescope from Staten Island, then re sent by the same system to Manhattan to warn of the approaching enemy. During the Revolutionary War, a similar system kept General Washington and Congress abreast of the movements of British ships in and out of New York Harbor. Again, in the War of 1812, this system was used.

Stock market speculators, wise in the ways of science, turned to a system of semaphores between the Highlands and a broker's building in New York. A semaphore was built on the Hill in 1826 by the Merchants Exchange Company.

The key to stock market success was in getting information first; a ship docking from Europe with good news sent stocks soaring, a ship with bad tidings sent the market sharply down. So, ships arriving off Sandy Hook were met by men in small boats, waiting to pick up news - good or bad - dropped over the side. The couriers rowed to shore - or, later, transferred the news to capsules on the legs of carrier pigeons - to report to the semaphore operators in Highlands, many hours before the ships could dock. The messages relayed by signal to New York, and across New Jersey to Philadelphia, gave the shrewd speculators the edge on the market.

In 1828, the first twin towers were built on the Hill, set on a northwest - southeast axis and about 320 feet apart. But almost before these original towers were completed, structural flaws appeared in the masonry and by the late 1850's agitation began for a new building to replace the one marred by bad materials and workmanship.

The present Twin Lights, a fortress - like structure of Belleville, New Jersey freestone brought in by barge and carted up the Hill, was constructed in 1861 to replace the dilapidated towers. (Though some writers and historians disclaim the title "Twin" due to the fact that one of the present towers is square and the other octagonal, it must be pointed out that it is the identical design of the lights that gives the structure its name, not the towers.) The Twin Lights were the first thing seen by the new liners viewing for the blue ribbon of the Atlantic in the days when everyone was competing for it.

There was a time, though, when the Twin Lights did actually become a single one. In 1883, (the date is sometimes given as 1841 and it stated that the Fresnel lens was installed in the previous twin towers - but the date was 1883) the French government undertook for exhibition at the Chicago World's Fair the construction of a gigantic light house lens, on the system designed by Augustin Fresnel many years before, but never previously put to use. It was a success, but it was so unwieldy, weighing as it did over seven tons, that it was easier to sell it to the U.S. government than to carry it back to France. After some hesitation the government decided that the most powerful light in the world belonged at the entrance to America's most important port. The 9,000,000 candle-power northern light of the twins winked out; the southern tower received the Fresnel, 25,000,000 candle-power and visible 22 miles at sea - and often 70 miles when reflected in a cloud bank. It's a light sailors still talk about!

In 1909, Guglielmo Marconi, the inventor of the system called wireless telegraphy, which he wished to demonstrate, was invited by the New York Herald to set up a station at the Twin Lights near the north tower so the Herald could be the first to have news of the 1909 America's Cup Races to be run off the New Jersey Coast.

Marconi accepted the invitation and the stage was set for the first test of the wireless in the Western Hemisphere. The steamship Ponce was rigged as the sending ship cruising at 15 knots off shore and Twin Lights the receiving station. The wireless worked, and the New York Herald scooped all other newspapers - making Marconi and the Twin Lights, once again, famous overnight.

Before World War II, the northern tower was the first place where experiments with radar were held. So successful were the tests that, soon after W.W. II, radar was the major tool of navigation and the government decided to decommission the Twin Lights and abandon the building as an operative light house.

The Borough of Highlands reached an agreement General Services Administration in 1952 to undertake the restoration and maintenance of the building and grounds and appointed, in 1953, the Twin Light Commission to actively work with t Lights Historical Society in this project.

In 1962, the State of New Jersey took over maintenance building - the Twin Lights became an official State Historic a historical and maritime museum was established the museum is now operated by the Twin Lights Historical Society and is open to visitors daily, except Monday, from Memorial Day through Labor Day.

Unfortunately, though. the Twin Lights Building and its grounds have recently been allowed to fall into a state of disrepair & deterioration. It is to be hoped that a renewed pride in Highland's most outstanding & famous historical landmark will arise to prepare Twin Lights to play a vital role in the United States' Bicentennial celebrations - 3 role in which it is entitled to play proudly, as it has throughout our history!

From out of the excitement of the Gay '90's, a spirit of independence began to grow within the citizens of the little town then known as Seaside. On the petition of sixteen legal voters~a bill was introduced into the New Jersey General Assembly on 13 February, Friday in 1900, to incorporate the Borough of Highlands. The bill passed and was signed on 22 March, 1900, and the district known as Seaside became the Borough of Highlands, capable of handling its own affairs and providing the necessary services and the privileges of democracy to its citizens.

The real history of Highlands as an entity (which included Minturn's Point, Lighthouse Hill, Parkertown, and Gravelly Point), rather than the romantic district called Seaside, begins with the incorporation of 1900 and the municipal acts that followed - they trace a pattern which shows what the life of those days must have been like. On 13 June, 1900, the Borough Council passed Ordinance VIII prohibiting horses, cows and pigs from running loose on the streets. and in September of the same year it was ordered that 3-inch hemlock and chestnut planking be used as curbs along the officially designated streets.

In April of 1906 the Borough received a favorable vote in a special election seeking permission to issue corporate bonds to the extent of $25,000.00 for the construction of a water works and a ant for supplying light. Confidence in the new community ran high enough so that the bonds were oversold, $30,000.00 worth at years being taken up.

At this time the only source of water in the low-lying lands was rough a system of pipes from which the springs in the hills were tapped, the water flowing by gravity to Miller Street, then to the center of town. School boys commonly made their pocket money delivering water to houses in 40 quart cans, following routes as boys in other towns did with newspapers.

Everybody carried personal kerosene lanterns when they went out at night in this period, but public lighting began on the same day that horses, cows and pigs were forbidden from the streets, with the purchase of three dozen lamp-posts to support kerosene lamps; it was some time before the gas light era began in Highlands or chickens and geese lost their freedom. At this period the houses on the hillside all had long flights of steps leading down to the business area, which was then clustered around Hillside and Bay Avenue. The constant fills due to the dredging of the river have since extended the town well seaward and changed its whole center of gravity.

The water-works went up in 1908, then replaced by a newer system in 1948. In 1910 the sale of ~4,500.00 worth of bonds paid for the purchase of a Borough Hall and for the beginnings of gas mains, stone curbing's and concrete sidewalks, but it was not until November, 1914 that Bay Avenue was authorized to be concreted from curb to curb. The Borough Hall's present building, including the Police Department and the Fire Department, was built on Bay Avenue in 1961.

In 1912, by a margin of only one vote, the historic community of Water Witch became a part of the Borough of Highlands.

The present form of government, councilmanic form under the Faulkner Act, Small Municipality Plan B, came into effect in 1956.

From its incorporation in 1900, through World War I, and up to the 1920's things remained relatively quiet in Highlands - though the visitors continued to come to fish, swim, eat good seafood and lounge in the sun. Many of today's Highlanders can remember growing up amidst the multitude of tent communities that dotted the shore, and spending their pennies on the merry-go-round and game arcades that lined the shore and avenues. At this time the three main industries in Highlands were fishing, clamming, and boating, but in the twenties a new industry arose providing the Highlanders with a period of adventure still talked about today.

In January of 1920 the Volstead Act was passed as a means of enforcing the 18th Amendment prohibiting the "manufacture, sale or transportation of intoxicating liquors." This Prohibition Amendment was the culmination of an anti-liquor fight begun by the American Temperance Society in 1815. But since the law did not specifically prohibit the consumption of liquor, many folks were encouraged and determined to obtain it, regardless of the law, and regardless of the post World War I movement to conserve grain. New Jersey, along with Connecticut and Rhode Island, continued to resist prohibition until 1922 when it alone became the last state to ratify it.

In theory New Jersey was then a "dry" state, but in reality this was far enough away from the truth to gain it the nickname of "Boot-Legers Paradise." (Boot-legger is a name derived from the practice of rum smugglers in which they occasionally slipped a bottle of the "good stuff" into the tops of their foul weather boots for future imbibement.)

"Rum-running" was a common practice for all of New Jersey's beachfront, but in 1920, when "rum row" was established off New York Bay, the town of Highlands became the main port for the in famous trade. Besides its location, the Highlands became famous because of its boat-building facilities and the daring of its rum runners, mostly fishermen and clamdiggers. The Jersey Skiff, designed and built in Highlands, became the primary craft to be used in the smuggling operations - its speed and strength made it capable of outrunning the Coast Guard gun boats in hot pursuit.

Leaving from secret boat ships in the dark of night the runners would cruise out to meet a ship waiting a few miles offshore with a cargo of whiskey from Canada or rum from the Caribbean Then the skiff, with its valuable cargo, would race through the night to return to the men waiting in secret rooms scattered throughout the High lands. When the signal lights from the beach were flashed the men would douse their pipes, end the tall tales they were weaving, and leave the warmth of the kerosene stove to go out into the murky morning darkness to claim their wares. A case of whiskey originating in Canada would cost the rum-runners $7.50; eventually on the illicit retail market the cost would be about 550.00 - a lucrative business to be sure.

Many restaurants and homes in Highlands had secret rooms in which to store the burlap bags filled with cases of booze, and some even had stills to produce their own. Most of these rooms, along with secret boat slips, stills and tunnels, have been forgotten - but the Highlanders will never forget Prohibition or the comical sight of Coast Guard boats being built in the same boat yards as the Jersey Skiffs with which they were supposed to compete in the rum trade.

Boat building was for a long time, even today, a prime industry in Highlands and one of the most celebrated crafts of all time, the Jersey Skiff, was designed and built here. The most renowned of these builders was the King Boat Works founded by Steward B. King in 1903. King, formerly a fisherman, secured over 200 patents on his designs, and his boat works continued to operate until very recently. All types of boats were built at Highlands, but the Jersey Skiff remains the most famous.

Highlands was the center of a re-awakened interest in sport fishing in the 1920's and Captain Tommy Gifford was a pioneer in the trade with his 28-foot Jersey Skiff powered by a Pierce-Arrow engine. Still today, scores of party boats, charter boats and private pleasure and commercial craft can be seen daily making their way northward to round Sandy Hook and out onto the open sea to try their luck with bluefish, striped bass, ling, whiting, mackerel, fluke or flounder. Everything necessary to pleasurable fishing is available in Highlands for those who go out on the boats or remain in the bay fishing from the beaches, docks or bulkheads.

Still, the Indian name Navesink lingers on, drawing people to this "good fishing place". The fish and seafood in the fish markets hereabout are so fresh that they either are still alive, or were swimming in the Atlantic Ocean no more than a few hours earlier. The proprietors are fishermen who catch or trap their own wares to sell to their retail or wholesale customers. They fish every night, except in fog or foul weather, and sell their catch as soon as it is cleaned in the morning. Highlands is still a fishing village at heart.

Clamming was a prime summer activity here for the Indians, and the white settlers learned the techniques of clamming from them. The first clammer to settle in Highlands after the Indians is thought to be one Sam Matthews who lived in a cave on the hill, but after the Revolutionary War many clammers and fishermen found the peaceful Sandy Hook Bay to their liking. At Parkertown, where the Navesink met the Bay (roughly the area from the present bridge to Miller Street), men lived off, by and for the clam. One writer said in 1890 that clams were to Parkertown "what the whale once was to Nantucket".

The following narrative was given in a book published in 1889: "Parkertown is an odd little hamlet whose population is engaged in clamming. The soul of this original community is wrapped up in clams. Parkertown is clamming, shelling, stringing or canning clams; devouring them, or dreaming of one or another of these acts. The idiosyncrasies of the clam are as well-known to Parkertowners as are the whims of a child to its parents. "Clam" is said to be the first word lisped by Parkertown babies. But while versed in all the arts of warfare upon the bivalve, this community has not shown itself as thoroughly versed in the arts of peace, and for this reason goes by several graphic but not very complimentary soubriquets."

Though this may be somewhat of an overzealous description, it does convey how important clamming is to the Highlands. It was the major industry and in the early days of this century as many as ten plants were in operation. The men would go out in the darkness t~ do the back-breaking work of raking the clams from their beds under the sandy river bottom. The clams were loaded by the bushel into the boats and taken to one of the plants where women employees (usually the clam diggers wives) opened them, removed the brown skin, and strung them on a "clam string" in groups of twenty-five, then barreled with ice and shipped to market.

Today the work of gathering the clams is done in the same back-breaking manner but the number of processing plants has been reduced to two. These plants use a depuration system, which purifies clams in 48 hours using clean salt water and ultraviolet rays. The of modern methods and technology has revived the clamming in try once threatened by water pollution and may once again clamming the major industry of Highlands.

Along with clamming, lobstering is a prime industry in Highlands. At many locations along the shore of the town huge stack lobster pots can be seen waiting to be loaded on the lobster boat and taken out to be dropped. The day begins for the lobstermen at 5 a.m. when they head to the open sea (as much as 17 miles shore) usually to the east or southeast of Sandy Hook. The pots (or traps) are strung on a line, usually 30 in series to a line, and carefully lowered to the bottom with each end secured to a maker buoy on the surface. The baited pots, a total of about 600 of them left for four days then hauled on board and their catch removed. Much work, muscle, experience and skill is required of those hearty men who follow the lobster trade.

After securing their catch and placing elastic on the lobsters' claws so that they will not devour each other, the lobstermen return to Highlands at about 4 p.m. to sell the catch to one of the seafood stores or restaurants. And many of the lobstermen spend their evenings anxiously trying to convince the Congress to affirm the 200 mile U.S. Coastal Limit in hopes of saving the threatened U.S. commercial fishing industry.

During Highlands 75 year history, many notable figures have made their homes here. Mickey Walker, "The Toy Bulldog" and one of the greatest middle-weight champions of all time, did his training in Highlands - as did many other figures in the sport of boxing.

Herbert Hunter, frequently called the baseball ambassador Japan, was a local personality who played on one of the numerous teams that were organized here. He took the first baseball team Japan and introduced the game there.

Fletcher Pratt, a historian and novelist, author of over 28 books, a long-time resident of Highlands was responsible for much of the information being gathered that now appears in this narrative.

And no list of notable Highlanders is complete without mentioning the incredible Gertrude Ederle. "Trudy" Ederle spent all of her summers in Highlands and it was here that she learned to swim at the beach on Miller Street. She swam from Sandy Hook to Highlands Bridge in two hours and forty minutes, while training for her famous English Channel swim in 1926. She became the first woman to swim the English Channel, and also the first to be given a ticker-tape parade up Broadway. Miss Ederle will be in Highlands this summer to take part in many of the 75th Anniversary celebrations, and a park at the Bridge was recently dedicated in her honor.

Those who enjoy swimming today can visit one of Highlands' many pools & public beaches or travel across the Highlands Bridge, a design award-winner built in 1931, to the Sandy Hook entrance to the new Gateway National Recreation Area.

As of January 1, 1975, all military installations on Sandy Hook (except for the U.S. Coast Guard) have been decommissioned and the Hook, with its thirteen miles of beaches and thirteen hundred acres of land, came under the control of the National Park Service and is now part of the Gateway National Recreation Area.

Its history of military defense is now over and for the first time in its recorded history the land will be open to the enjoyment of the public.

Many of the beaches are open for swimming, surfing and fishing activities; nature trails are open to hikers; and educational and recreational facilities and programs are available. Even though sixteen million people live within an 80 mile radius of the peninsula, Sandy Hook's marsh, dune and forest areas are relatively undisturbed.

The main visitor information station is located at the Spermaceti Cove Visitor Center. A visit to this magnificent new recreational facility is a must for all visitors to Highlands and a valuable asset to all Highlanders.

Though the tiny borough of Highlands has swelled considerably in population and many new buildings have been added - some good, some not so good - there still exists within the Highlanders a spirit of small-town community - proud and respectful of their distinguished past history. Another new era is opening for Highlands with the coming of its 75th Anniversary. As the Gateway National Recreation Area grows to its full potential Highlands will once again be a major resort community, as the already famous restaurants of Highlands grow in esteem and new ones are added it is certain that the town will truly become the "Seafood Capital Of The East."

In hopeful anticipation of the many new visitors of this year, and the promise of the future, many Highlanders are doing their best to help to restore the natural beauty and attractions and improve the physical appearance of the Borough, while maintaining the characteristic spirit that is so much "Highlands."

"Nothing - wind, storm, hurricane, even people - changes the Highlands much.", is as true today as when first written over fifty years ago. The essential things will never change: the loveliness of the hills in early morning sunlight or when darkened by stormy sky, the loneliness and ever-changing moods of the ocean and rivers, the joy of meeting once again the friends made last summer, the lingering after-thought of huge plates of steamed clams and draft beer by the keg, hot afternoons on the beach and returning to the peaceful serenity of home after journeys to the boardwalks further south, to the racetrack or far beyond. Something - perhaps the spirit left here by so many travelers through the centuries - draws all who spend time here back again to Highlands.

For those who return in 1975 there is a program of festivities planned for the summer like never before in Highlands. And for those who call Highlands home there is the growing opportunity to make it a model for the rest of the Jersey Shore to change what needs changing, to improve where necessary (especially for the well being of the young and the old) and to pay tribute to what has made the Borough of Highlands and its people such an important part of the Gateway to the New World.

The writing of this brief history has been a labor dedicated to the people of Highlands, and especially to my Grandfather, who first came here before the turn of the Century and spent every summer of his 90-year life; and to Mr. Harry Bovenizer of Water Witch a 63 year resident of Highlands.

Esteban Gómez also known as Estevan Gómez, born Estêvão Gomes (c. 1483 Porto, † 1538 Paraguay River), was a Portuguese cartographer and explorer who sailed at the service of Spain in the fleet of Ferdinand Magellan, having deserted the expedition before reaching the Strait of Magellan, returning to Spain in May 1521. In 1524 he explored Nova Scotia province sailing South through Maine, where he entered New York Harbor, the Hudson River and eventually reached Florida in August 1525. As a result of his expedition, the 1529 Diogo Ribeiro world map outlines the East coast of North America almost perfectly.

Esteban Gómez also known as Estevan Gómez, born Estêvão Gomes (c. 1483 Porto, † 1538 Paraguay River), was a Portuguese cartographer and explorer who sailed at the service of Spain in the fleet of Ferdinand Magellan, having deserted the expedition before reaching the Strait of Magellan, returning to Spain in May 1521. In 1524 he explored Nova Scotia province sailing South through Maine, where he entered New York Harbor, the Hudson River and eventually reached Florida in August 1525. As a result of his expedition, the 1529 Diogo Ribeiro world map outlines the East coast of North America almost perfectly.

Virtually the war had long been over, although the definitive treaty of peace was not formally signed until September 3, 1783. Yet, non the less, did Monmouth county Tories and Refugees, in sheer vindictiveness of revenge, continue in their course of spoilation, destruction, and murder to the bitter end. The burning ot Toms-River was the last of their exploits having even the semblance of military character, but sporadic crimes long continued to be committed. Cases in point are the killing of Davenport, pursued with hue and cry, by exasperated patriots, and the butchery of sleeping Americans by Bacon, told on page 80 of this volume.

Virtually the war had long been over, although the definitive treaty of peace was not formally signed until September 3, 1783. Yet, non the less, did Monmouth county Tories and Refugees, in sheer vindictiveness of revenge, continue in their course of spoilation, destruction, and murder to the bitter end. The burning ot Toms-River was the last of their exploits having even the semblance of military character, but sporadic crimes long continued to be committed. Cases in point are the killing of Davenport, pursued with hue and cry, by exasperated patriots, and the butchery of sleeping Americans by Bacon, told on page 80 of this volume. Huddy Handed Over To Lippencott

Huddy Handed Over To Lippencott

Wargamers know Pratt as the inventor of a set of rules for naval wargaming before the Second World War. This was known as the "The Fletcher Pratt Naval War Game" and involved dozens of tiny wooden ships, built on a scale of one inch to 50 feet. These were spread over the floor of Pratt's apartment and their maneuvers were calculated via a complex mathematical formula. Noted author and artist Jack Coggins was a frequent participant in Pratt's Navy Game, and de Camp met him through his wargaming group.

Wargamers know Pratt as the inventor of a set of rules for naval wargaming before the Second World War. This was known as the "The Fletcher Pratt Naval War Game" and involved dozens of tiny wooden ships, built on a scale of one inch to 50 feet. These were spread over the floor of Pratt's apartment and their maneuvers were calculated via a complex mathematical formula. Noted author and artist Jack Coggins was a frequent participant in Pratt's Navy Game, and de Camp met him through his wargaming group. spider, which when it enters its burrow pulls the hatch shut behind it. The club was later fictionalized as the Black Widowers in a series of mystery stories by Isaac Asimov. Pratt himself was fictionalized in one story, "To the Barest", as the Widowers’ founder, Ralph Ottur.

spider, which when it enters its burrow pulls the hatch shut behind it. The club was later fictionalized as the Black Widowers in a series of mystery stories by Isaac Asimov. Pratt himself was fictionalized in one story, "To the Barest", as the Widowers’ founder, Ralph Ottur.

Why is it that a reef off Big Pine Key in the Florida Keys, that is popular with divers, is named after the picturesque coastal town, Looe in Cornwall, England? Answer, Looe Reef is the site where HMS Looe, a 44-gun fifth rate frigate was shipwrecked after running onto the reef in 1744. As a result the ships crew found themselves stranded on a remote shoal in enemy territory, facing the possibility of capture by the Spanish or worst still Calusa Indians, who treated the English with contempt and would most likely have murdered them.

Why is it that a reef off Big Pine Key in the Florida Keys, that is popular with divers, is named after the picturesque coastal town, Looe in Cornwall, England? Answer, Looe Reef is the site where HMS Looe, a 44-gun fifth rate frigate was shipwrecked after running onto the reef in 1744. As a result the ships crew found themselves stranded on a remote shoal in enemy territory, facing the possibility of capture by the Spanish or worst still Calusa Indians, who treated the English with contempt and would most likely have murdered them. Henry Clinton was a British general who fought in the American Revolution. He was Commander-in-Chief at the time that the colonies were lost. Not much is known of his early life and few details are known of his life after the war.

Henry Clinton was a British general who fought in the American Revolution. He was Commander-in-Chief at the time that the colonies were lost. Not much is known of his early life and few details are known of his life after the war. “The Water-Witch” is a 1830 novel by James Fenimore Cooper. Set in 17th century New York, and the surrounding sea, the novel depicts the abduction of a woman, Alida de Barbérie, by the pirate captain of the brigantine, Water Witch, and the subsequent pursuit of that elusive ship by her suitor, Captain Ludlow.

“The Water-Witch” is a 1830 novel by James Fenimore Cooper. Set in 17th century New York, and the surrounding sea, the novel depicts the abduction of a woman, Alida de Barbérie, by the pirate captain of the brigantine, Water Witch, and the subsequent pursuit of that elusive ship by her suitor, Captain Ludlow.

Mickey Walker, who won the world welterweight and middleweight boxing titles and also fought some of the sport's top heavyweights, died yesterday morning at Freehold Area Hospital in Freehold, N.J. He was 79 years old.

Mickey Walker, who won the world welterweight and middleweight boxing titles and also fought some of the sport's top heavyweights, died yesterday morning at Freehold Area Hospital in Freehold, N.J. He was 79 years old. In his 160 bouts, he scored 60 knockouts, many with his powerful left hook, and won 33 by decision, with four draws. He lost 11 by decision, three on fouls, five by knockouts. Forty-five more bouts were no decisions, and one was ruled no contest.

In his 160 bouts, he scored 60 knockouts, many with his powerful left hook, and won 33 by decision, with four draws. He lost 11 by decision, three on fouls, five by knockouts. Forty-five more bouts were no decisions, and one was ruled no contest. But after that he decided to become a professional boxer. Travels With Kearns

But after that he decided to become a professional boxer. Travels With Kearns Sir Edmund Andros, (born Dec. 6, 1637, London, Eng.—died Feb. 24, 1714, London), English administrator in North America who made an abortive attempt to stem growing colonial independence by imposing a kind of supercolony, the Dominion of New England.

Sir Edmund Andros, (born Dec. 6, 1637, London, Eng.—died Feb. 24, 1714, London), English administrator in North America who made an abortive attempt to stem growing colonial independence by imposing a kind of supercolony, the Dominion of New England. THE first highways in New Jersey of which there are any records or traditions were Indian paths. These are often referred to in early deeds and in the old records of commissioners for laying out roads. In a very old map which accompanies the edition of the Elizabethtown Bill in Chancery, published by James Parker in New York in 1747 (which map he reproduced from a still more ancient one, called "Popple’s Large Map of the English Colonies in America"), there is a tracing of one of the most notable of these Indian paths, known as the "Minisink Path," and which extended from the Navesink Highlands on the ocean to Minisink Island in the Delaware, a distance of about seventy-five miles. This path started from Navesink, near the mouth of Shrewsbury River or Inlet, in Monmouth County, and ran northwesterly through Middletown to the Raritan River, in Middlesex County, crossing the river at Kent’s Neck, near Crab Island, between Amboy and the mouth of South River. After crossing the Raritan the path ran north-northwest in its course, crossing the head of Rahway River, till it reached a point about six miles west of Elizabethtown Point, when it ran a short distance due north, and the remainder of its route north-northwest, passing over the mountains to the west of Springfield and Newark, and traversing the whole of Morris and Essex Counties in a north-northwest course to Minisink Island in the Delaware, below Port Jervis, and near the point of intersection of Sussex County in New Jersey with Orange County in New York. This northerly limit of the Minisink path was a part of the favorite hunting-ground of the Minisink Indians, which extended throughout the entire valley lying north of the Blue Mountains in Pennsylvania, stretching from the Wind Gap in that State into New York near the Hudson. We may indulge the fancy that this path was devised to enable the "upper ten" among the aborigines to enjoy the "season" at Long Branch, and to lay up stores of shells and fish. At Amboy, and at intervals along the sea-coast from Shrewsbury to Barnegat, there still remain relics of these periodical visits of the Indians, consisting of various-sized mounds of opened oyster-shells, many of which are from six to twenty feet in height, having a corresponding base, and built in a conical form. Some of these are now covered with alluvial, which has been in course of deposit upon them for centuries. There are also remains of shell-banks, made up of other than oyster-shells, being of the shells of clams and periwinkles, out of the former of which the Indians made their black (and most valuable) wampum. It is believed that the shell-banks or mounds of this kind are the refuse of Indian wampum manufactories.

THE first highways in New Jersey of which there are any records or traditions were Indian paths. These are often referred to in early deeds and in the old records of commissioners for laying out roads. In a very old map which accompanies the edition of the Elizabethtown Bill in Chancery, published by James Parker in New York in 1747 (which map he reproduced from a still more ancient one, called "Popple’s Large Map of the English Colonies in America"), there is a tracing of one of the most notable of these Indian paths, known as the "Minisink Path," and which extended from the Navesink Highlands on the ocean to Minisink Island in the Delaware, a distance of about seventy-five miles. This path started from Navesink, near the mouth of Shrewsbury River or Inlet, in Monmouth County, and ran northwesterly through Middletown to the Raritan River, in Middlesex County, crossing the river at Kent’s Neck, near Crab Island, between Amboy and the mouth of South River. After crossing the Raritan the path ran north-northwest in its course, crossing the head of Rahway River, till it reached a point about six miles west of Elizabethtown Point, when it ran a short distance due north, and the remainder of its route north-northwest, passing over the mountains to the west of Springfield and Newark, and traversing the whole of Morris and Essex Counties in a north-northwest course to Minisink Island in the Delaware, below Port Jervis, and near the point of intersection of Sussex County in New Jersey with Orange County in New York. This northerly limit of the Minisink path was a part of the favorite hunting-ground of the Minisink Indians, which extended throughout the entire valley lying north of the Blue Mountains in Pennsylvania, stretching from the Wind Gap in that State into New York near the Hudson. We may indulge the fancy that this path was devised to enable the "upper ten" among the aborigines to enjoy the "season" at Long Branch, and to lay up stores of shells and fish. At Amboy, and at intervals along the sea-coast from Shrewsbury to Barnegat, there still remain relics of these periodical visits of the Indians, consisting of various-sized mounds of opened oyster-shells, many of which are from six to twenty feet in height, having a corresponding base, and built in a conical form. Some of these are now covered with alluvial, which has been in course of deposit upon them for centuries. There are also remains of shell-banks, made up of other than oyster-shells, being of the shells of clams and periwinkles, out of the former of which the Indians made their black (and most valuable) wampum. It is believed that the shell-banks or mounds of this kind are the refuse of Indian wampum manufactories.